Twenty to the Mile: The Overland Telegraph Line

PREFACE

One hundred and fifty years ago, a small group of talented technicians and bushmen gathered under a tall pole near Frew’s Ironstone Ponds, deep in the Northern Territory bush. At 12 noon, their leader, Robert Patterson, climbed a ladder and grasped the two ends of the telegraph line in order to join them.

He promptly received an electric shock.

This delayed the joining by a few minutes. Patterson found a handkerchief and tried again. Wrapping the wire with the cloth, he soldered the southward facing line of wire to its mate. The O.T.L. then stretched 2,839 kilometres[2] as a single wire from Palmerston on the north coast to Port Augusta on the south, and 300 kilometres more to Adelaide. It joined a network of telegraph wires spread across the eastern states from far Northern Queensland to Tasmania.

In Palmerston, John Archibald Graham Little, the Senior Telegraph Officer, waited in the log hut that was his telegraph office. The importance of the occasion must have impressed him. Dr Ralph Millner, then acting Government Resident, had written out a congratulatory message to be sent to the Governor of South Australia. Little tested his Morse key, and double checked. The ‘dashes and dots’ of Morse code would travel at electric speed to telegraph repeater stations across the continent to his south. Then, powered by large banks of batteries, operators at each of eleven stations on the line would keep the message moving. Each operator needed to record the message exactly as it was sent, and then resend it. They were well trained.

Messages had been flying back and forth along the south and north wires for months as they grew further north from Port Augusta and further south from Palmerston and, as the lines drew closer, excitement grew. The first message from Alice Springs to Adelaide was sent on 30 December 1871. Eight months later, field operator and future stationmaster, Charles Johnston, sent a telegram from the end of the wire on the southern side:

… wired yesterday, 4½ miles; to-day 6½ miles. If the other parties are making as good speed as is reported, it will not be long before the gap is closed, and daily communication opened between Palmerston and Adelaide[5].

A week before the joining of the line, Postmaster-General Charles Todd set up a camp at Barrow’s Creek Telegraph Station near Central Mount Stuart. By Morse code, he kept the government informed of the line’s progress, and they in turn fed the news to the newspapers:

… The line is working splendidly. I feel assured the Government will acknowledge that since the work was resumed at the end of the wet season no time has been lost, and that with even all the vexatious delays and mishaps in the Northern Territory, the erection of 2,000 miles of telegraph through the centre of Australia in less than two years is not bad work, especially when it is remembered that we have had to procure our materials from England. It is to be hoped the cable will be repaired by the time our wire joins….

The overland line was going to be fine, but the undersea cable to Java had problems, three days later:

… We have now only two short wire gaps; one will close on Monday or Tuesday, the other most probably on Wednesday or Thursday at latest. The cable unfortunately is still interrupted. The Investigator is trying to pick it up near the coast of Java; but the prevailing monsoon, which will soon moderate, has probably hitherto retarded operations.

In the last few weeks before the lines met, a horse express run by John Lewis, could cross the gap in ever lessening time. This had allowed the first message from Adelaide to London to be transmitted on 25 June 1872. Messages were transferred by hand to each end of the wire and communication between Darwin and London and Adelaide was live. It was a slow but effective solution that worked well until the undersea cable broke.

In the meantime, Todd could sit and calculate when the lines would meet. It finally happened near John McDouall Stuart’s old camp at Frew’s Ironstone Ponds. As the ends closed together, John Little in Darwin, and Charles Todd at Central Mount Stuart, prepared to send their first messages. The repeater stations were manned and ready.

At ten past twelve Patterson joined the wire and the messaging started. As promised in the days before, at 1 p.m. precisely, the first official electric telegram arrived in Adelaide from Port Darwin. Following that a string of congratulatory messages was transmitted from consuls and vice-consuls, politicians, and senior public servants. All were gathered and published the next day in the newspapers and the words thrilled the people of Adelaide. The most quoted text came from Todd:

… We have this day or within two years from the date it was commenced, completed a line of 2,000 miles long through the very centre of Australia a few years ago a terra incognita and supposed to be a desert, and I have the satisfaction of seeing the successful completion of a scheme I officially advanced 14 years ago

The newspapers were enthusiastic, and the telegraph departments partied. A public holiday was announced, and banquets were planned.

The OTL is held by many, even these days, as no less significant for nineteenth-century Australia as that ‘giant leap’ event was to the world in the twentieth century. Indeed, many claim it was the greatest engineering achievement of the nineteenth century.

The men gathered around the pole in the bush celebrated too. They fired 21 shots from their revolvers and smashed a brandy bottle against the pole. The bottle, it is said, was filled frugally with tea–no one was about to waste good brandy, even for such a momentous occasion.

Communication between the cities of the eastern seaboard, through Adelaide to Darwin and back, now took minutes, instead of weeks. And, after the undersea cable was repaired by men on the Investigator, at midnight on 20 October, the line opened at 9 a.m. for communication with London. Just imagine what a difference that made for business investors, war watchers, news hounds, and English patriots keeping in touch with ‘Old Blighty’. Australia's geographic isolation from the rest of the world and the ‘tyranny of distance’ were immediately and forever ameliorated. News now arrived from London within seven hours, rather than two or three months. It was then picked up and broadcast by the newspapers. Businessmen placed orders, did their banking, and gathered market information. Colonial governments received directives directly from the British parliament. Prosperity and wealth blossomed.

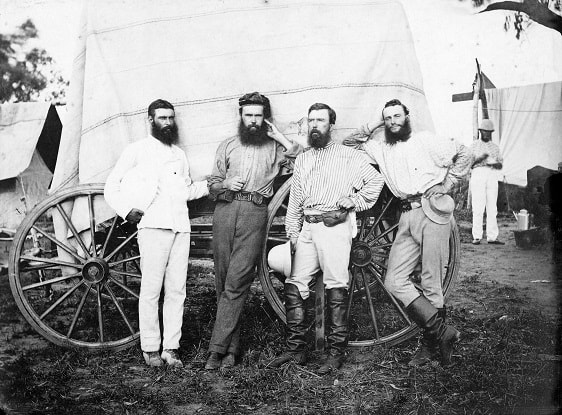

They were exciting times. This book celebrates the sesquicentenary of the joining of the wires on 22 August 1872. It tells stories of the hundreds of men, and occasional women, who worked on the line, used it, relied on it for survival–or died on it during the 19th century.

The names of the men in the construction teams appear in the Appendix. No doubt some are missing, as are the unrecorded names of most of the Aboriginal men and women who also appear in the story. The full history of the greatest engineering feat of nineteenth century Australia is yet to be finished, but I offer this tome as a step on the way.

[2] The exact length of the OTL is difficult to determine. This number comes from a simple adding of Charles Todd’s stated section lengths in miles between Port Augusta and Port Darwin and converting to kilometres. Some sources round the distance to 3,000 km. Others measure the line from Adelaide to Port Darwin and call it 3,200 km (for example see Australian Museum, Australian Geographic). Engineers Australia agree and use 3,178 km on their commemorative plaque on the joining pole at Frew’s Ponds but the NT Government, on one website, enthusiastically claim 3,600 km! Charles Todd said the distance from Adelaide to Port Darwin is 1,973 miles or 3,175.2 kilometres.

One hundred and fifty years ago, a small group of talented technicians and bushmen gathered under a tall pole near Frew’s Ironstone Ponds, deep in the Northern Territory bush. At 12 noon, their leader, Robert Patterson, climbed a ladder and grasped the two ends of the telegraph line in order to join them.

He promptly received an electric shock.

This delayed the joining by a few minutes. Patterson found a handkerchief and tried again. Wrapping the wire with the cloth, he soldered the southward facing line of wire to its mate. The O.T.L. then stretched 2,839 kilometres[2] as a single wire from Palmerston on the north coast to Port Augusta on the south, and 300 kilometres more to Adelaide. It joined a network of telegraph wires spread across the eastern states from far Northern Queensland to Tasmania.

In Palmerston, John Archibald Graham Little, the Senior Telegraph Officer, waited in the log hut that was his telegraph office. The importance of the occasion must have impressed him. Dr Ralph Millner, then acting Government Resident, had written out a congratulatory message to be sent to the Governor of South Australia. Little tested his Morse key, and double checked. The ‘dashes and dots’ of Morse code would travel at electric speed to telegraph repeater stations across the continent to his south. Then, powered by large banks of batteries, operators at each of eleven stations on the line would keep the message moving. Each operator needed to record the message exactly as it was sent, and then resend it. They were well trained.

Messages had been flying back and forth along the south and north wires for months as they grew further north from Port Augusta and further south from Palmerston and, as the lines drew closer, excitement grew. The first message from Alice Springs to Adelaide was sent on 30 December 1871. Eight months later, field operator and future stationmaster, Charles Johnston, sent a telegram from the end of the wire on the southern side:

… wired yesterday, 4½ miles; to-day 6½ miles. If the other parties are making as good speed as is reported, it will not be long before the gap is closed, and daily communication opened between Palmerston and Adelaide[5].

A week before the joining of the line, Postmaster-General Charles Todd set up a camp at Barrow’s Creek Telegraph Station near Central Mount Stuart. By Morse code, he kept the government informed of the line’s progress, and they in turn fed the news to the newspapers:

… The line is working splendidly. I feel assured the Government will acknowledge that since the work was resumed at the end of the wet season no time has been lost, and that with even all the vexatious delays and mishaps in the Northern Territory, the erection of 2,000 miles of telegraph through the centre of Australia in less than two years is not bad work, especially when it is remembered that we have had to procure our materials from England. It is to be hoped the cable will be repaired by the time our wire joins….

The overland line was going to be fine, but the undersea cable to Java had problems, three days later:

… We have now only two short wire gaps; one will close on Monday or Tuesday, the other most probably on Wednesday or Thursday at latest. The cable unfortunately is still interrupted. The Investigator is trying to pick it up near the coast of Java; but the prevailing monsoon, which will soon moderate, has probably hitherto retarded operations.

In the last few weeks before the lines met, a horse express run by John Lewis, could cross the gap in ever lessening time. This had allowed the first message from Adelaide to London to be transmitted on 25 June 1872. Messages were transferred by hand to each end of the wire and communication between Darwin and London and Adelaide was live. It was a slow but effective solution that worked well until the undersea cable broke.

In the meantime, Todd could sit and calculate when the lines would meet. It finally happened near John McDouall Stuart’s old camp at Frew’s Ironstone Ponds. As the ends closed together, John Little in Darwin, and Charles Todd at Central Mount Stuart, prepared to send their first messages. The repeater stations were manned and ready.

At ten past twelve Patterson joined the wire and the messaging started. As promised in the days before, at 1 p.m. precisely, the first official electric telegram arrived in Adelaide from Port Darwin. Following that a string of congratulatory messages was transmitted from consuls and vice-consuls, politicians, and senior public servants. All were gathered and published the next day in the newspapers and the words thrilled the people of Adelaide. The most quoted text came from Todd:

… We have this day or within two years from the date it was commenced, completed a line of 2,000 miles long through the very centre of Australia a few years ago a terra incognita and supposed to be a desert, and I have the satisfaction of seeing the successful completion of a scheme I officially advanced 14 years ago

The newspapers were enthusiastic, and the telegraph departments partied. A public holiday was announced, and banquets were planned.

The OTL is held by many, even these days, as no less significant for nineteenth-century Australia as that ‘giant leap’ event was to the world in the twentieth century. Indeed, many claim it was the greatest engineering achievement of the nineteenth century.

The men gathered around the pole in the bush celebrated too. They fired 21 shots from their revolvers and smashed a brandy bottle against the pole. The bottle, it is said, was filled frugally with tea–no one was about to waste good brandy, even for such a momentous occasion.

Communication between the cities of the eastern seaboard, through Adelaide to Darwin and back, now took minutes, instead of weeks. And, after the undersea cable was repaired by men on the Investigator, at midnight on 20 October, the line opened at 9 a.m. for communication with London. Just imagine what a difference that made for business investors, war watchers, news hounds, and English patriots keeping in touch with ‘Old Blighty’. Australia's geographic isolation from the rest of the world and the ‘tyranny of distance’ were immediately and forever ameliorated. News now arrived from London within seven hours, rather than two or three months. It was then picked up and broadcast by the newspapers. Businessmen placed orders, did their banking, and gathered market information. Colonial governments received directives directly from the British parliament. Prosperity and wealth blossomed.

They were exciting times. This book celebrates the sesquicentenary of the joining of the wires on 22 August 1872. It tells stories of the hundreds of men, and occasional women, who worked on the line, used it, relied on it for survival–or died on it during the 19th century.

The names of the men in the construction teams appear in the Appendix. No doubt some are missing, as are the unrecorded names of most of the Aboriginal men and women who also appear in the story. The full history of the greatest engineering feat of nineteenth century Australia is yet to be finished, but I offer this tome as a step on the way.

[2] The exact length of the OTL is difficult to determine. This number comes from a simple adding of Charles Todd’s stated section lengths in miles between Port Augusta and Port Darwin and converting to kilometres. Some sources round the distance to 3,000 km. Others measure the line from Adelaide to Port Darwin and call it 3,200 km (for example see Australian Museum, Australian Geographic). Engineers Australia agree and use 3,178 km on their commemorative plaque on the joining pole at Frew’s Ponds but the NT Government, on one website, enthusiastically claim 3,600 km! Charles Todd said the distance from Adelaide to Port Darwin is 1,973 miles or 3,175.2 kilometres.