VICTORIA SETTLEMENT

PORT ESSINGTON

1838-49

|

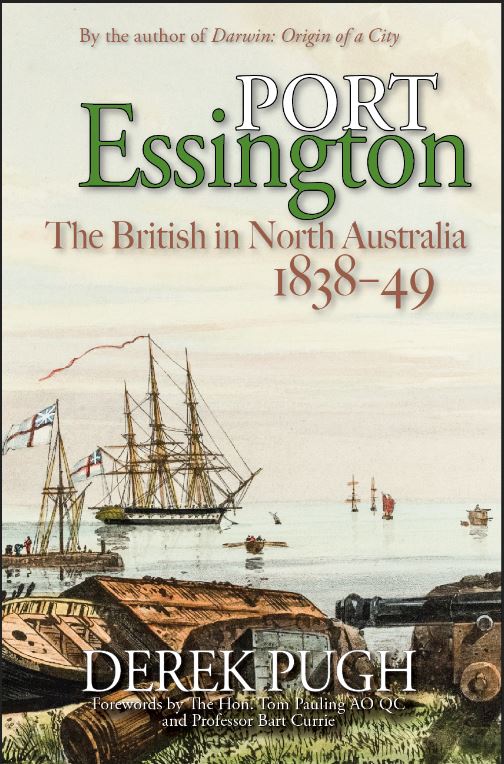

For many of the Royal Marines sent to Port Essington, life was a living hell of malaria, scurvy, termites, shipwrecks, cyclones, boredom, isolation, and death. For one man it was the ‘most useless, miserable, ill-managed hole in Her Majesty’s dominions’ which deserved ‘all the abuse that has ever been heaped upon it’. But it wasn’t always so: In the beginning, French visitors shared their best Bordeaux wines and partied at Government House; small boats raced in regattas across the harbour; men played cricket; and the gardens grew the best pineapples in the southern hemisphere. Led by the stoic Captain John McArthur for 11 years, this is the story of the rise and fall of a peaceful little British village in the most distant part of the empire, and of how the chief occupation of the survivors became grave digging. ‘a splendid read full of heartbreak, hope, despair, ambition and resilience’ (Tom Pauling AO QC). October 2020. Buy this book. |

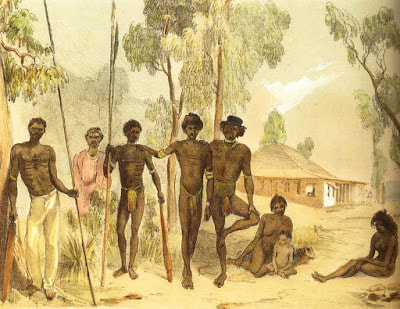

Iwaidja |

HMS Pelorus |

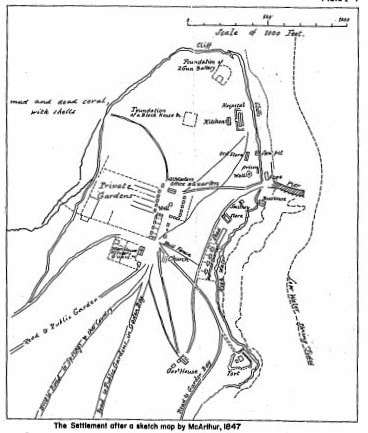

Victoria Settlement |

CHAPTER 8. THE HEROINE AND THE PRIEST

Fresh from taking the triumphant Dr Ludwig Leichhardt and his party to Sydney, the schooner Heroine was returning to the north. She was in company with two other supply ships: Sapphire and Enchantress. On board the Heroine, Captain Martin Mackenzie was the most experienced commander of the three, so he led the way through the Great Barrier Reef. Unfortunately, his navigation was not good enough.

On 4 April 1846, the three ships were near the Cumberland Islands, some 20 miles west of where Mackenzie thought they were and travelling at 8 or 9 knots. Then, without warning – just before 1 A.M. – the Heroine hit rocks with ‘such violence that the foretopmast went over the side’ (Sweatman, 1847).

Eight of her people were killed. Reverend Nicholas Hogan and Reverend James Fagan were asleep in a cabin below and they drowned in their beds. Mr Earl, the brother of George Earl, managed to get out on deck with his wife. Earl tied himself to his wife, but the rope he chose was a part of the rigging. As a result, they were dragged to the bottom as the ship went down. Also drowned were an unnamed Chinese man and three of the Javanese crew.

On board the ship were ‘5 natives of Port Essington’, one of whom was ‘Jack White’. With other passengers and the seamen, they swam to the rocks, or to a small boat that was under tow. They were later rescued by the boats of the Sapphire and the Enchantress.

Another priest, and three women, managed to cling to the main topmast as the ship sank. They were rescued by Nelson, the chief mate’s Newfoundland dog. The dog swam them, one by one, to safety on the reef.

Captain Mackenzie swam the wrong way – in the dark and confusion, he headed out to sea. Tragically, he tied his infant daughter to his back, but the little girl died from exposure before morning and Mackenzie reluctantly let her drift away. When dawn broke, 5 hours later, he could see the Sapphire in the distance. Luckily, he was spotted by the mate, just as the ship was bearing up, and rescued.

Mackenzie lost his child and his life savings. Also gone were 300 sovereigns the ship was transporting to Port Essington to pay the garrison. George Lambrick, the paymaster, was eagerly awaiting them because the men were paid in cash, but the sovereigns were now lying on the sea floor. The Government usually only sent cash on warships, but since the Royalist had left the port, Victoria had been without one. In fact, there was no warship anywhere in Australia at that time (Spillett, 1972), and the men had not been paid for months.

There were 40 survivors from the wreck, and they were transferred to the Enchantress and delivered to Port Essington on 13 April 1846.

The priest who owed his life to Nelson the Newfoundland dog, was Father Angelo Confalonieri, a Catholic missionary from Lake Garda in Northern Italy. He had been sent from Rome by Pope Gregory XVI with 20 other Irish, French, and Italian missionaries to evangelise Australia (McKenna, 2016). He had been appointed the ‘Vicar-General of Port Essington’ in Perth but now was destitute. He had lost everything in the wreck, including his two assistants – the Reverends Hogan and Fagan. Despite this, Sweatman was impressed by Confalonieri. He described him as ‘very gentlemanly and well educated ... liberal minded and tolerant on all points of religion’.

On arrival in the port, the destitute priest threw himself on Captain McArthur’s mercy, asking him for any help he could give. He promised that his superior in Perth, Bishop John Brady, would repay McArthur for any receipts he produced. Confalonieri owned nothing. McArthur took pity on him and provided him with food and clothing, paper, pencils, and accommodation. Confalonieri was not a British subject, so McArthur was unsure of how much help he could officially give, so he took the responsibility on himself. He paid for a month’s rations and generously offered to continue providing them until Confalonieri could provide for himself.

Confalonieri was a clever linguist and the only European of the time to study the Iwaidja language in depth (Harris, 1985). He was extremely short-sighted and had lost his glasses in the shipwreck, but he could charm and communicate well with people. However, there were still great difficulties, such as mischievous intents among his informants: when he was collecting vocabulary, the larrikins among the Iwaidja would sometimes teach him obscenities instead of the words he wanted:

‘When the poor padre came to address the natives, he wondered how it was that they laughed so at his sermons’ (Sweatman, 1847).

Confalonieri’s mission was to live with the Aborigines and convert them to Christianity. Originally unaware of the tribes’ semi-nomadic life, he had planned to set himself up in a ‘village’ near the Alligator Rivers. However, his plans changed when he learned there were no permanent villages anywhere in the Top End and McArthur convinced him to remain closer to Victoria for safety. A hut was built for him on the opposite side of the harbour near Black Point, about 20 km from Victoria. He lived there with a young Iwaidja man, known as Jim Crow, who worked as his language assistant and translator, and probably as a general servant.

Confalonieri made a short victualling journey to the Ki Islands on the Bramble when Lieutenant Yule, accompanied by the Castlereagh, sailed there to buy pigs and other food items .

Confalonieri had money loaned to him by McArthur, and he bought a small boat called a sampan to use for his mission. Unfortunately, he didn’t have it long – it was soon stolen by two English sailors who deserted from the Castlereagh whilst they were still in the Islands. Lieutenant Yule refused to wait whilst the sailors were located because he had 98 wild pigs breaking out of their bamboo holding pens and fighting ‘like cocks jumping up at each other’, on the deck of his ship. He therefore needed to return to Port Essington as quickly as possible. Even so, two pigs managed to jump overboard and drown before the crew had even weighed anchor. Six more were lost on the way.

Confalonieri’s troubles were not over. According to Sweatman, he was helpless in the most ordinary domestic matters. For example, he did not know how to mix and cook flour. He also had to beg the garrison for everything, including a spoon. They hardly had one to spare – but it was ‘miserable to eat pease [sic] soup with a fork’, he said (Sweatman, 1847).

Once the shipment of pigs was unloaded and the paperwork done to transfer them to Lambrick’s domain, Confalonieri was left to settle into his hut, and the Bramble was taken to anchor near Point Record.

The ship was suffering from a plague of cockroaches, which were an ‘intolerable nuisance’. Sweatman said it was impossible:

... to sleep below for them, for apart from the nuisance of having such disgusting animals crawling over one they used actually to eat away the skin from our extremities while we slept... they flew about like birds, I have even seen the lights put out by them... (Sweatman, 1847).

Sweatman had done a study on the effects of the cockroaches on the ship’s bread supply. He had taken a 112-pound bag from the stores at Victoria, had the officers sign and seal it in the ship’s bread room, and left it alone for 20 days while they sailed to the Ki Islands and back. When it was again weighed, it totalled 65 pounds, and ‘the bag was eaten to rags and the biscuits like honeycomb’. Sweatman worked out that he had lost 3000 pounds of bread since they had left Sydney.

The ship’s crew had tried smoking the cockroaches out, and this had worked for a while, but by June 1846 they were back in force. Lieutenant Yule paid the ship’s boys to collect them, by the pint, between dark and 8 P.M. each night. They would catch at least two or three pints for their efforts, every day. This started to become too expensive for the lieutenant, so a new plan was needed.

At the beginning of August, the Bramble was moored off Point Record. The crew then unloaded all the stores and equipment onto the beach and erected a sail as a ten. They then lived under it for the next three months.

Clearing out the ship was a big job, and it took until 14 August before the Bramble was completely emptied. Then, at high tide, she was taken around to some sand flats and a ‘scuttle’ was cut in her side at low tide. She then filled with water from the incoming tide:

... At high water, she was completely covered above the tops of the roundhouses abaft; and the cockroaches came up by millions to take refuge on the rigging, and the crew stood by with buckets: ... to wash them down and a regular water frolic took place: the sea was covered with the dead who were washed ashore in heaps where the natives gathered them up in handfuls to eat them! (Sweatman, 1847).

The ship was drained with the tide, the scuttle closed, and the ship was pumped dry. A few worm-eaten planks were then replaced, while stoves burned below to dry the lower decks. Then she was completely cleaned and repainted, and the stores examined minutely to ensure not a single cockroach was allowed back on board. More than 500 gallons of cockroaches were shovelled out; and about the same amount were washed away by the sea!

All this was done in the dry air of August, and a pleasant camp was had by all, despite the annoyance of clouds of little black flies during the day, and mosquitoes at night. Sweatman tells of regularly swimming off Point Record, and although no ‘alligators’ ever appeared, to be sure they were safe the Englishmen regularly:

...collected a dozen or twenty women and children and made them bathe with us, as well for the fun we used to have with them, swimming, diving, playing leapfrog &c as to make a good noise and hubbub in the water & so frighten the sharks away. Moreover, people say, though I do not know if it’s true, that a shark always prefers a blackfellow to a white if he has a choice... (Sweatman, 1847).

The process of emptying and drowning the Bramble, then drying her out and repacking her, took a little under three months. She was finally ready to return to Sydney cockroach free. But the drowning process had not killed the eggs. Soon the insects were swarming once again through the holds and cabins. The whole process had to be repeated the next summer, in Sydney.

As the Bramble left on 12 September 1846, on board was Lieutenant William Wright, invalided out because of worsening epilepsy.

Meanwhile, at Black Point, Father Angelo Confalonieri became more adept at speaking Iwaidja. He was more and more accepted by the people. They respected him for his kind manner and willingness to join them in their ‘wandering and desultory’ way of life. He happily travelled unarmed, but remained ‘childlike’, because he needed to be cared for every step of the way.

The priest found that the Iwaidja adults were hard to pin down for religious education. Nevertheless, he:

... continued to teach the blackfellows to say a few prayers, of whose meanings they had not the remotest notion: indeed I was told that they were occasionally to be heard repeating them in the square of the settlement with many gestures as rather a good joke than otherwise ... (Huxley, 1848).

He collected together as many of the children of the Limbakarajia tribe as he could induce to remain in the neighbourhood. He endeavoured to instruct them in the elements of his religion, and taught them to repeat prayers in Latin, and follow him in some of the ceremonious observances of the Roman Catholic Church. Like other children this amused them, and so long as they were well fed and supplied with tobacco, everything went on as he could desire (MacGillivray, 15 October 1845).

There were several drugs brought to Australia from Macassar on the annual voyages: alcohol, tobacco, betel nut and possibly opium. It was probably for the use of the captains and crew at first (though religious Muslim would not have been drinkers). But, when the Macassans observed how welcome alcohol and tobacco were to the tribes along the coast, more were brought for trade or payment for labour (Brady, 2020).

Many Aboriginal men would have seen opium smoking in Makassar first hand — hundreds of men undertook ‘the grand tour’ to Makassar with the praus, stayed there for the off-season, then returned the following year. Some may even have married there and stayed for years. In 1845, MacGillivray wrote that Aborigines ‘frequently’ accompanied the Macassans (MacGillivray, 1852). Thus, not only could they have observed and participated in opium smoking, they also would have had the opportunity to obtain the pipes and could return to Australia with them. Then, because opium was mostly unavailable on the north coast in the 1840s, the pipes became a preferred way of smoking tobacco. Sweatman was bemused by this:

... they smoke to excess, every child that can walk has a pipe in his gills and I have seen men get absolutely intoxicated on smoke alone ... (Sweatman, 1847).

As part of his mission of converting Aborigines to Christianity, Confalonieri taught Iwaidja children to pray in English. Decades later, ‘Flash Poll’ could still recite the Lord’s Prayer. However, Sweatman says Confalonieri eventually despaired of his mission:

... had they any idolatry of their own, he said, they might have rooted it out and taught them Christianity instead, but having no idea of religion whatever, he feared it would be impossible to make them understand anything about it ... (Sweatman, 1847).

Confalonieri’s plan, after he had fully mastered the language, was spread ‘The Word’, among the tribes as far west as the Alligator Rivers and east to Van Dieman’s Gulf. He worked out that the Iwaidja people were actually divided into seven tribes, and he drew a map of their tribal areas, and collected dialect variances in the Iwaidja language

Unfortunately, Confalonieri did not impress all the Iwaidja. One day, several elders from the Black Point area tricked him into checking his boat one day. While he was away, they ransacked his hut and stole from him. When Confalonieri reported the men to the commandant, McArthur identified them as men who had already been expelled from the settlement for bad behaviour. Then the elders took offence. They asked what right did a man who lived alone have to talk about them in that way? They then declared themselves to be enemies, although they never fulfilled the evident threats that they became, and Confalonieri continued to travel among the people unarmed.

Occasionally the priest was visited by men from the settlement. Young John McArthur kept a short log in the McArthurs’ notebook of a sailing trip he made to see him in the Gipsy, on a particularly wet weekend in 1847:

Friday 26th Feby [1847] Started from the pier about 8 AM towed out past Minto Head. A very heavy squall of wind and rain about 9 P.M. reached out to and anchored at the triangles, much rain during the night. Saturday 27 got under weigh about 5.30 am as we got out wind freshened to a smart gale with continued squalls of rain arrived at Don Angelo’s about 11 am obliged to let go two pigs of ballast to hold the boat the Don says it is the worst weather he has had this monsoon. Last night he expected his house to fall. I dined with him and as he said the worst weather was generally in the night and the boat had already driven considerably, I determined to get out of his place before dark and get anchorage on the weather shore.

Perhaps foreshadowing the disastrous government policies of the next century, Confalonieri came to believe that the only way the natives were to become civilised was to remove the children from their families and raise them as British citizens. McArthur agreed, but he was having troubles of his own at the time. Like Lambrick and others in the settlement, he had employed an Iwaidja boy to work around his house and run errands for him. But through his role as a civil magistrate he had ‘interfered’ in the affairs of several Iwaidja men who were involved with a tribal killing of men from Goulburn Island. The Iwaidja told him it was none of his business, and he should refrain from anything other than issues to do with whites. They said they expected to be executed if they killed a white man, but they had the right to deal with their own people as their law allowed. As tensions rose, the boys who worked in the settlement left and either refused to return or were not permitted to by their families.

When the wet season arrived at the end of 1846, Confalonieri stayed near his hut, endured the rains and the insects, while he prepared his word lists. He also translated the Lord’s Prayer, the Hail Mary, the Creed, and the Catechism of Christian Doctrine (which contains the Ten Commandments), into the local Iwaidja dialect. When the dry season followed in 1847, he was sufficiently well known to attract a large number of Aborigines seeking help from him for an influenza epidemic that hit them hard (Pryor, 1990). Doctor Tilston regularly crossed the harbour from the Coral Bay convalescents’ resort to help him, and they saved more than a few lives.

Confalonieri attended his mission for just over two years, living most of it in his little Black Point hut, or travelling across Cobourg Peninsula with the Iwaidja. But, in June 1848, a boat happened to pass the point and a marine dropped in to see him, only to find him sick in bed, with a fever that had already burned for a week. He was rushed to the hospital and the care of Dr Crawford. He never recovered and he died on 9 June 1848. His bones still lie in a lonely grave on Cobourg Peninsula. All his bones, that is, except one. His scapula was removed and dried according to his dying wish (Pryor, 1990). It was then sent with a small cross to his sister, near Lake Garda in Italy, and was placed in their church’s ossuary.

Confalonieri remained a topic of conversation for the remainder of the settlement’s existence. Thomas Huxley never met him, but was curious:

... Thinking about the desolate life of the man, I said to Crawford ... ‘I suppose this man was a thorough enthusiast, for it is difficult to imagine what else could have supported him through such trials’. Crawford told me that I quite deceived myself, that he had had much conversation with the priest, and that he seemed wholly without religious feeling, well acquainted with theology and a strong stickler for the doctrine of his church, but more like an advocate than a believer ... he was in an especial sense a soldier of his church, i.e. like most soldiers he did his duty religiously but cared not two straws for the quarrel in which he fought (Huxley, 1848).

MacGillivray saw the priest’s diary and discovered that much of Confalonieri’s time was spent waiting. He had written a letter asking for help. It was published in the Catholic Press on 6 March 1847, and the result was enough donations to fully kit him out in his mission for years to come. He then waited in hope for everything to arrive. Hope faded to despair when they did not:

... While leading this lonely life he seems gradually to have given way to gloomy despondency. I recollect one passage in his diary (which I once saw for an hour) where he expresses himself thus: "Another year has gone by, and with it all signs of the promised vessel. Oh! God, even hope seems to have deserted me”.

At length, a vessel from Sydney arrived, bringing a large supply of stores of every kind for the mission, but it was too late, for Father Anjello [sic] and his sorrows were alike resting in the tomb. One day news came that he was ill; a boat was sent immediately for him and found him dying. He was removed to the settlement and next day he breathed his last – another, but not the last victim to the climate. His deathbed was described to me as having been a fearful scene. He exhibited the greatest horror of death, and in his last extremity blasphemously denied that there was a God! (MacGillivray, 1852).

By the time the donated equipment arrived in Port Essington on the John and Charlotte, poor Confalonieri had been dead and buried for nearly six months. Among the cargo was a large packing case marked ‘piano’. Everyone thought it was a ‘veritable piano forte, sent to console Don Angelo’s solitary hours and perhaps help his performance of the mass’ (Huxley, 1848), and they were curious to see it. Some of the sailors swore they heard jarred strings from within, as the crate was shifted from the ship.

The most curious was Captain Owen Stanley who had an ‘especial vocation for prying into all concerns’. He ordered the crate opened, but no ‘rosewood grand’ was to be seen. Instead it was a box crammed full of ‘priest’s vestments and other baubles’. The inscription on the box, when examined more closely, said ‘Posa Piano’ ... Handle Carefully. Unfortunately, the vestments were of no use to anybody.

Confalonieri is remembered in Darwin in the name of Angelo Street, and a plaque on the wall of St Mary’s Cathedral commemorates him as the Territory’s first Catholic missionary. Also, in Palmerston there is a Confalonieri Park.

Fresh from taking the triumphant Dr Ludwig Leichhardt and his party to Sydney, the schooner Heroine was returning to the north. She was in company with two other supply ships: Sapphire and Enchantress. On board the Heroine, Captain Martin Mackenzie was the most experienced commander of the three, so he led the way through the Great Barrier Reef. Unfortunately, his navigation was not good enough.

On 4 April 1846, the three ships were near the Cumberland Islands, some 20 miles west of where Mackenzie thought they were and travelling at 8 or 9 knots. Then, without warning – just before 1 A.M. – the Heroine hit rocks with ‘such violence that the foretopmast went over the side’ (Sweatman, 1847).

Eight of her people were killed. Reverend Nicholas Hogan and Reverend James Fagan were asleep in a cabin below and they drowned in their beds. Mr Earl, the brother of George Earl, managed to get out on deck with his wife. Earl tied himself to his wife, but the rope he chose was a part of the rigging. As a result, they were dragged to the bottom as the ship went down. Also drowned were an unnamed Chinese man and three of the Javanese crew.

On board the ship were ‘5 natives of Port Essington’, one of whom was ‘Jack White’. With other passengers and the seamen, they swam to the rocks, or to a small boat that was under tow. They were later rescued by the boats of the Sapphire and the Enchantress.

Another priest, and three women, managed to cling to the main topmast as the ship sank. They were rescued by Nelson, the chief mate’s Newfoundland dog. The dog swam them, one by one, to safety on the reef.

Captain Mackenzie swam the wrong way – in the dark and confusion, he headed out to sea. Tragically, he tied his infant daughter to his back, but the little girl died from exposure before morning and Mackenzie reluctantly let her drift away. When dawn broke, 5 hours later, he could see the Sapphire in the distance. Luckily, he was spotted by the mate, just as the ship was bearing up, and rescued.

Mackenzie lost his child and his life savings. Also gone were 300 sovereigns the ship was transporting to Port Essington to pay the garrison. George Lambrick, the paymaster, was eagerly awaiting them because the men were paid in cash, but the sovereigns were now lying on the sea floor. The Government usually only sent cash on warships, but since the Royalist had left the port, Victoria had been without one. In fact, there was no warship anywhere in Australia at that time (Spillett, 1972), and the men had not been paid for months.

There were 40 survivors from the wreck, and they were transferred to the Enchantress and delivered to Port Essington on 13 April 1846.

The priest who owed his life to Nelson the Newfoundland dog, was Father Angelo Confalonieri, a Catholic missionary from Lake Garda in Northern Italy. He had been sent from Rome by Pope Gregory XVI with 20 other Irish, French, and Italian missionaries to evangelise Australia (McKenna, 2016). He had been appointed the ‘Vicar-General of Port Essington’ in Perth but now was destitute. He had lost everything in the wreck, including his two assistants – the Reverends Hogan and Fagan. Despite this, Sweatman was impressed by Confalonieri. He described him as ‘very gentlemanly and well educated ... liberal minded and tolerant on all points of religion’.

On arrival in the port, the destitute priest threw himself on Captain McArthur’s mercy, asking him for any help he could give. He promised that his superior in Perth, Bishop John Brady, would repay McArthur for any receipts he produced. Confalonieri owned nothing. McArthur took pity on him and provided him with food and clothing, paper, pencils, and accommodation. Confalonieri was not a British subject, so McArthur was unsure of how much help he could officially give, so he took the responsibility on himself. He paid for a month’s rations and generously offered to continue providing them until Confalonieri could provide for himself.

Confalonieri was a clever linguist and the only European of the time to study the Iwaidja language in depth (Harris, 1985). He was extremely short-sighted and had lost his glasses in the shipwreck, but he could charm and communicate well with people. However, there were still great difficulties, such as mischievous intents among his informants: when he was collecting vocabulary, the larrikins among the Iwaidja would sometimes teach him obscenities instead of the words he wanted:

‘When the poor padre came to address the natives, he wondered how it was that they laughed so at his sermons’ (Sweatman, 1847).

Confalonieri’s mission was to live with the Aborigines and convert them to Christianity. Originally unaware of the tribes’ semi-nomadic life, he had planned to set himself up in a ‘village’ near the Alligator Rivers. However, his plans changed when he learned there were no permanent villages anywhere in the Top End and McArthur convinced him to remain closer to Victoria for safety. A hut was built for him on the opposite side of the harbour near Black Point, about 20 km from Victoria. He lived there with a young Iwaidja man, known as Jim Crow, who worked as his language assistant and translator, and probably as a general servant.

Confalonieri made a short victualling journey to the Ki Islands on the Bramble when Lieutenant Yule, accompanied by the Castlereagh, sailed there to buy pigs and other food items .

Confalonieri had money loaned to him by McArthur, and he bought a small boat called a sampan to use for his mission. Unfortunately, he didn’t have it long – it was soon stolen by two English sailors who deserted from the Castlereagh whilst they were still in the Islands. Lieutenant Yule refused to wait whilst the sailors were located because he had 98 wild pigs breaking out of their bamboo holding pens and fighting ‘like cocks jumping up at each other’, on the deck of his ship. He therefore needed to return to Port Essington as quickly as possible. Even so, two pigs managed to jump overboard and drown before the crew had even weighed anchor. Six more were lost on the way.

Confalonieri’s troubles were not over. According to Sweatman, he was helpless in the most ordinary domestic matters. For example, he did not know how to mix and cook flour. He also had to beg the garrison for everything, including a spoon. They hardly had one to spare – but it was ‘miserable to eat pease [sic] soup with a fork’, he said (Sweatman, 1847).

Once the shipment of pigs was unloaded and the paperwork done to transfer them to Lambrick’s domain, Confalonieri was left to settle into his hut, and the Bramble was taken to anchor near Point Record.

The ship was suffering from a plague of cockroaches, which were an ‘intolerable nuisance’. Sweatman said it was impossible:

... to sleep below for them, for apart from the nuisance of having such disgusting animals crawling over one they used actually to eat away the skin from our extremities while we slept... they flew about like birds, I have even seen the lights put out by them... (Sweatman, 1847).

Sweatman had done a study on the effects of the cockroaches on the ship’s bread supply. He had taken a 112-pound bag from the stores at Victoria, had the officers sign and seal it in the ship’s bread room, and left it alone for 20 days while they sailed to the Ki Islands and back. When it was again weighed, it totalled 65 pounds, and ‘the bag was eaten to rags and the biscuits like honeycomb’. Sweatman worked out that he had lost 3000 pounds of bread since they had left Sydney.

The ship’s crew had tried smoking the cockroaches out, and this had worked for a while, but by June 1846 they were back in force. Lieutenant Yule paid the ship’s boys to collect them, by the pint, between dark and 8 P.M. each night. They would catch at least two or three pints for their efforts, every day. This started to become too expensive for the lieutenant, so a new plan was needed.

At the beginning of August, the Bramble was moored off Point Record. The crew then unloaded all the stores and equipment onto the beach and erected a sail as a ten. They then lived under it for the next three months.

Clearing out the ship was a big job, and it took until 14 August before the Bramble was completely emptied. Then, at high tide, she was taken around to some sand flats and a ‘scuttle’ was cut in her side at low tide. She then filled with water from the incoming tide:

... At high water, she was completely covered above the tops of the roundhouses abaft; and the cockroaches came up by millions to take refuge on the rigging, and the crew stood by with buckets: ... to wash them down and a regular water frolic took place: the sea was covered with the dead who were washed ashore in heaps where the natives gathered them up in handfuls to eat them! (Sweatman, 1847).

The ship was drained with the tide, the scuttle closed, and the ship was pumped dry. A few worm-eaten planks were then replaced, while stoves burned below to dry the lower decks. Then she was completely cleaned and repainted, and the stores examined minutely to ensure not a single cockroach was allowed back on board. More than 500 gallons of cockroaches were shovelled out; and about the same amount were washed away by the sea!

All this was done in the dry air of August, and a pleasant camp was had by all, despite the annoyance of clouds of little black flies during the day, and mosquitoes at night. Sweatman tells of regularly swimming off Point Record, and although no ‘alligators’ ever appeared, to be sure they were safe the Englishmen regularly:

...collected a dozen or twenty women and children and made them bathe with us, as well for the fun we used to have with them, swimming, diving, playing leapfrog &c as to make a good noise and hubbub in the water & so frighten the sharks away. Moreover, people say, though I do not know if it’s true, that a shark always prefers a blackfellow to a white if he has a choice... (Sweatman, 1847).

The process of emptying and drowning the Bramble, then drying her out and repacking her, took a little under three months. She was finally ready to return to Sydney cockroach free. But the drowning process had not killed the eggs. Soon the insects were swarming once again through the holds and cabins. The whole process had to be repeated the next summer, in Sydney.

As the Bramble left on 12 September 1846, on board was Lieutenant William Wright, invalided out because of worsening epilepsy.

Meanwhile, at Black Point, Father Angelo Confalonieri became more adept at speaking Iwaidja. He was more and more accepted by the people. They respected him for his kind manner and willingness to join them in their ‘wandering and desultory’ way of life. He happily travelled unarmed, but remained ‘childlike’, because he needed to be cared for every step of the way.

The priest found that the Iwaidja adults were hard to pin down for religious education. Nevertheless, he:

... continued to teach the blackfellows to say a few prayers, of whose meanings they had not the remotest notion: indeed I was told that they were occasionally to be heard repeating them in the square of the settlement with many gestures as rather a good joke than otherwise ... (Huxley, 1848).

He collected together as many of the children of the Limbakarajia tribe as he could induce to remain in the neighbourhood. He endeavoured to instruct them in the elements of his religion, and taught them to repeat prayers in Latin, and follow him in some of the ceremonious observances of the Roman Catholic Church. Like other children this amused them, and so long as they were well fed and supplied with tobacco, everything went on as he could desire (MacGillivray, 15 October 1845).

There were several drugs brought to Australia from Macassar on the annual voyages: alcohol, tobacco, betel nut and possibly opium. It was probably for the use of the captains and crew at first (though religious Muslim would not have been drinkers). But, when the Macassans observed how welcome alcohol and tobacco were to the tribes along the coast, more were brought for trade or payment for labour (Brady, 2020).

Many Aboriginal men would have seen opium smoking in Makassar first hand — hundreds of men undertook ‘the grand tour’ to Makassar with the praus, stayed there for the off-season, then returned the following year. Some may even have married there and stayed for years. In 1845, MacGillivray wrote that Aborigines ‘frequently’ accompanied the Macassans (MacGillivray, 1852). Thus, not only could they have observed and participated in opium smoking, they also would have had the opportunity to obtain the pipes and could return to Australia with them. Then, because opium was mostly unavailable on the north coast in the 1840s, the pipes became a preferred way of smoking tobacco. Sweatman was bemused by this:

... they smoke to excess, every child that can walk has a pipe in his gills and I have seen men get absolutely intoxicated on smoke alone ... (Sweatman, 1847).

As part of his mission of converting Aborigines to Christianity, Confalonieri taught Iwaidja children to pray in English. Decades later, ‘Flash Poll’ could still recite the Lord’s Prayer. However, Sweatman says Confalonieri eventually despaired of his mission:

... had they any idolatry of their own, he said, they might have rooted it out and taught them Christianity instead, but having no idea of religion whatever, he feared it would be impossible to make them understand anything about it ... (Sweatman, 1847).

Confalonieri’s plan, after he had fully mastered the language, was spread ‘The Word’, among the tribes as far west as the Alligator Rivers and east to Van Dieman’s Gulf. He worked out that the Iwaidja people were actually divided into seven tribes, and he drew a map of their tribal areas, and collected dialect variances in the Iwaidja language

Unfortunately, Confalonieri did not impress all the Iwaidja. One day, several elders from the Black Point area tricked him into checking his boat one day. While he was away, they ransacked his hut and stole from him. When Confalonieri reported the men to the commandant, McArthur identified them as men who had already been expelled from the settlement for bad behaviour. Then the elders took offence. They asked what right did a man who lived alone have to talk about them in that way? They then declared themselves to be enemies, although they never fulfilled the evident threats that they became, and Confalonieri continued to travel among the people unarmed.

Occasionally the priest was visited by men from the settlement. Young John McArthur kept a short log in the McArthurs’ notebook of a sailing trip he made to see him in the Gipsy, on a particularly wet weekend in 1847:

Friday 26th Feby [1847] Started from the pier about 8 AM towed out past Minto Head. A very heavy squall of wind and rain about 9 P.M. reached out to and anchored at the triangles, much rain during the night. Saturday 27 got under weigh about 5.30 am as we got out wind freshened to a smart gale with continued squalls of rain arrived at Don Angelo’s about 11 am obliged to let go two pigs of ballast to hold the boat the Don says it is the worst weather he has had this monsoon. Last night he expected his house to fall. I dined with him and as he said the worst weather was generally in the night and the boat had already driven considerably, I determined to get out of his place before dark and get anchorage on the weather shore.

Perhaps foreshadowing the disastrous government policies of the next century, Confalonieri came to believe that the only way the natives were to become civilised was to remove the children from their families and raise them as British citizens. McArthur agreed, but he was having troubles of his own at the time. Like Lambrick and others in the settlement, he had employed an Iwaidja boy to work around his house and run errands for him. But through his role as a civil magistrate he had ‘interfered’ in the affairs of several Iwaidja men who were involved with a tribal killing of men from Goulburn Island. The Iwaidja told him it was none of his business, and he should refrain from anything other than issues to do with whites. They said they expected to be executed if they killed a white man, but they had the right to deal with their own people as their law allowed. As tensions rose, the boys who worked in the settlement left and either refused to return or were not permitted to by their families.

When the wet season arrived at the end of 1846, Confalonieri stayed near his hut, endured the rains and the insects, while he prepared his word lists. He also translated the Lord’s Prayer, the Hail Mary, the Creed, and the Catechism of Christian Doctrine (which contains the Ten Commandments), into the local Iwaidja dialect. When the dry season followed in 1847, he was sufficiently well known to attract a large number of Aborigines seeking help from him for an influenza epidemic that hit them hard (Pryor, 1990). Doctor Tilston regularly crossed the harbour from the Coral Bay convalescents’ resort to help him, and they saved more than a few lives.

Confalonieri attended his mission for just over two years, living most of it in his little Black Point hut, or travelling across Cobourg Peninsula with the Iwaidja. But, in June 1848, a boat happened to pass the point and a marine dropped in to see him, only to find him sick in bed, with a fever that had already burned for a week. He was rushed to the hospital and the care of Dr Crawford. He never recovered and he died on 9 June 1848. His bones still lie in a lonely grave on Cobourg Peninsula. All his bones, that is, except one. His scapula was removed and dried according to his dying wish (Pryor, 1990). It was then sent with a small cross to his sister, near Lake Garda in Italy, and was placed in their church’s ossuary.

Confalonieri remained a topic of conversation for the remainder of the settlement’s existence. Thomas Huxley never met him, but was curious:

... Thinking about the desolate life of the man, I said to Crawford ... ‘I suppose this man was a thorough enthusiast, for it is difficult to imagine what else could have supported him through such trials’. Crawford told me that I quite deceived myself, that he had had much conversation with the priest, and that he seemed wholly without religious feeling, well acquainted with theology and a strong stickler for the doctrine of his church, but more like an advocate than a believer ... he was in an especial sense a soldier of his church, i.e. like most soldiers he did his duty religiously but cared not two straws for the quarrel in which he fought (Huxley, 1848).

MacGillivray saw the priest’s diary and discovered that much of Confalonieri’s time was spent waiting. He had written a letter asking for help. It was published in the Catholic Press on 6 March 1847, and the result was enough donations to fully kit him out in his mission for years to come. He then waited in hope for everything to arrive. Hope faded to despair when they did not:

... While leading this lonely life he seems gradually to have given way to gloomy despondency. I recollect one passage in his diary (which I once saw for an hour) where he expresses himself thus: "Another year has gone by, and with it all signs of the promised vessel. Oh! God, even hope seems to have deserted me”.

At length, a vessel from Sydney arrived, bringing a large supply of stores of every kind for the mission, but it was too late, for Father Anjello [sic] and his sorrows were alike resting in the tomb. One day news came that he was ill; a boat was sent immediately for him and found him dying. He was removed to the settlement and next day he breathed his last – another, but not the last victim to the climate. His deathbed was described to me as having been a fearful scene. He exhibited the greatest horror of death, and in his last extremity blasphemously denied that there was a God! (MacGillivray, 1852).

By the time the donated equipment arrived in Port Essington on the John and Charlotte, poor Confalonieri had been dead and buried for nearly six months. Among the cargo was a large packing case marked ‘piano’. Everyone thought it was a ‘veritable piano forte, sent to console Don Angelo’s solitary hours and perhaps help his performance of the mass’ (Huxley, 1848), and they were curious to see it. Some of the sailors swore they heard jarred strings from within, as the crate was shifted from the ship.

The most curious was Captain Owen Stanley who had an ‘especial vocation for prying into all concerns’. He ordered the crate opened, but no ‘rosewood grand’ was to be seen. Instead it was a box crammed full of ‘priest’s vestments and other baubles’. The inscription on the box, when examined more closely, said ‘Posa Piano’ ... Handle Carefully. Unfortunately, the vestments were of no use to anybody.

Confalonieri is remembered in Darwin in the name of Angelo Street, and a plaque on the wall of St Mary’s Cathedral commemorates him as the Territory’s first Catholic missionary. Also, in Palmerston there is a Confalonieri Park.