|

ESCAPE CLIFFS: The First Northern Territory Expedition 1864-66.

Included are the first photographs taken in the Northern Territory. Out NOW in shops or click Buy Derek Pugh Books on line or phone The Bookshop Darwin on 08 8941 3489.489. |

This is a story of the start of South Australian colonisation of the Northern Territory. It is a story of greed, courage, exploration, murder, wasted efforts, life and death struggles, insubordination, incredible seamanship, and extraordinary bushmanship, amid government bungling and Aboriginal resistance.

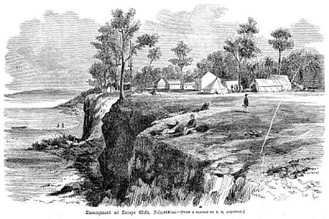

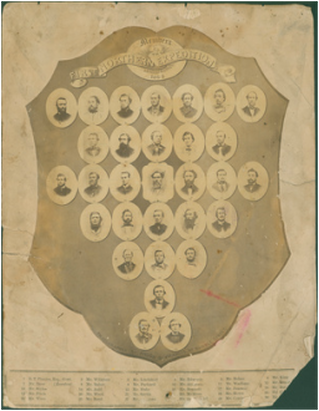

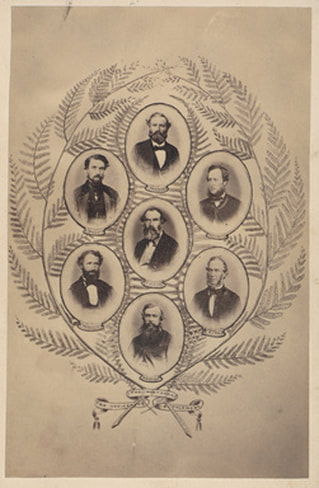

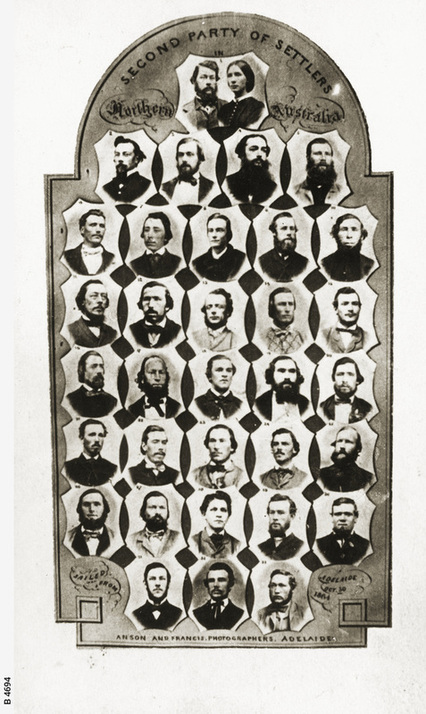

Escape Cliffs was an attempt by South Australia to become the premier state of the country. It would open up a trading route across the country to Asia, and exploit the agricultural and mining opportunities of the interior. It would be at no cost to the state, as the land was sold, unsurveyed and unseen, to investors prior to the First Northern Territory Expedition even setting out. But then, as the saying goes, the fight really started… The settlement at Escape Cliffs was the fourth attempt to settle the north by Europeans. The first three, at Fort Dundas, Fort Wellington, and Port Essington, were military settlements designed to preclude other European nations from claiming a part of the north coast of Australia for their own colonies, and as a contact point for trade with the four hundred or so Macassan Prahus. Escape Cliffs was different to the British military settlements, in that it was a part of an attempt by an Australian Colony, South Australia, to become the premier state of the country. The South Australian government, in competition with Queensland, had taken over the land to the north, calling it the Northern Territory of South Australia, in 1863. Events then moved remarkably quickly. The South Australians wanted to open a trading route across the country to Asia and exploit any agricultural and mining opportunities they could from the interior. They hoped to do this at no cost to themselves, and therefore sold the land, unseen and unsurveyed, prior to the First Northern Territory Expedition even setting out. A part of the plan, which linked South Australia to the rest of the world with an overland telegraph line, would mean that the point of entry of news and business, for the whole of Australia, would be through Adelaide. Thus the colony had national significance, and was of great interest to the big states of New South Wales and Victoria, particularly. There was much work to do, and no time was wasted. Within a few months, the forty members of the First Northern Territory Expedition were recruited and sent, in three ships, to survey and establish a city on the north coast. Led by a retired politician and ex-soldier, Colonel Boyle Finniss, and including a mostly poorly selected group of officers and men, it was funded by investors from Adelaide and London, and farewelled with optimism, but it was doomed to fail from the outset. Arguments between powerful personalities begun even before the ships were loaded, and they continued, more and more bitterly, even after reinforcements were sent later the same year. The city was to be called ‘Palmerston’, as was its successor. Although it is now called, since 1911, Darwin. Darwin’s modern satellite city, some 20 kilometres south, is the third settlement to carry the name Palmerston. The early military settlements along the north coast existed too early to be photographed, and in the 1860s photography was still in its infancy, particularly in remote areas. There were few cameras anywhere but, incredibly, two found their way to Escape Cliffs. The few surviving photographs from these cameras are remarkable because they were taken in the Northern Territory within a very few months of its declaration and takeover by South Australia. There is, therefore a photographic record of the Northern Territory’s entire colonial existence, and all the known photographs of the Escape Cliffs years are reproduced in this book. Escape Cliffs, at the mouth of the huge Adelaide River, is remote and unreachable without a boat or a helicopter, so it’s not on any tourist itinerary, and few visitors climb up to the brick and metal remains of the first Northern Territory capital. As a result, its story is one that is rarely told, but those who wonder at the origin of the names of the Finniss, King and Howard Rivers, Litchfield National Park, Manton Dam, Fred’s Pass, Lake Bennett, and dozens of Darwin’s streets will find the answers here. They were named after real people, with aspirations and hopes for the future, who lived in extraordinary times. This book is about them and those times. Derek Pugh 2017 |

|

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

|

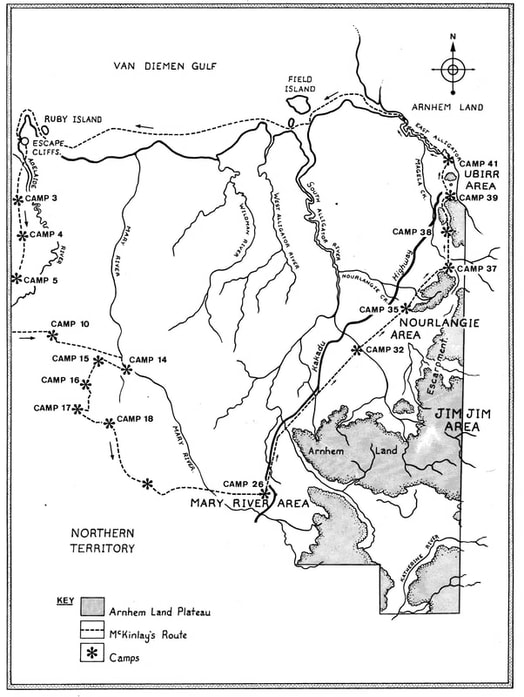

MAP: McKinlay's route from Escape Cliffs to the East Alligator River.

This map is published in the book and marked "with permission Kim Lockwood" as he also uses it in his book "Big John".

It should be correctly referenced as "based on field research conducted by Dr LFS Browne". I apologise for the oversight and thank Lloyd Brown for his valuable research.

For more on this incredible story read "John McKinlay and the Mary River Mud", Occasional Paper #43 (State Library NT), by Lloyd Browne:

http://www.territorystories.nt.gov.au/jspui/bitstream/10070/153144/1/occpaper43.pdf

This map is published in the book and marked "with permission Kim Lockwood" as he also uses it in his book "Big John".

It should be correctly referenced as "based on field research conducted by Dr LFS Browne". I apologise for the oversight and thank Lloyd Brown for his valuable research.

For more on this incredible story read "John McKinlay and the Mary River Mud", Occasional Paper #43 (State Library NT), by Lloyd Browne:

http://www.territorystories.nt.gov.au/jspui/bitstream/10070/153144/1/occpaper43.pdf